Introduction

Not long ago I stumbled upon the signature of the flatten method on Option:

def flatten[B](implicit ev: A <:< Option[B]): Option[B]

I don’t know about you, but I knew about implicit parameter lists, implicit resolution, and even type bounds. But this funny <:< “sad-with-a-hat” operator was entirely new to me!

Smart people have written about it years ago, but it’s clear that we are talking about a feature which is not well-known and poorly documented, even though it is available since Scala 2.8. So this article is about figuring out what it means and how it works.

The following deconstruction turns out to be fairly long, but even though <:< itself may not be useful to every Scala programmer, it touches a surprisingly large number of Scala features which most Scala programmers should know.

What it does and how it’s useful

If you search the Scala standard library, you find a few other occurrences of <:<, in particular:

on Option:

def orNull[A1 >: A](implicit ev: Null <:< A1): A1

on Traversable (via traits like GenTraversableOnce):

def toMap[K, V](implicit ev: A <:< (K, V)): Map[K, V]

on Either:

def joinRight[A1 >: A, B1 >: B, C](implicit ev: B1 <:< Either[A1, C]): Either[A1, C]

on Try:

def flatten[U](implicit ev: T <:< Try[U]): Try[U]

You notice that, in all these examples, <:< is used in the same way:

- there is an implicit parameter list, with a single parameter called

ev

- the type of this parameter is of the form

Type1 <:< Type2

The lowdown is that this pattern tells the compiler:

Make sure that Type1 is a subtype of Type2, or else report an error.

This is part of a feature called generalized type constraints. There is another similar construct, =:=, which tells the compiler:

Make sure that Type1 is exactly the same as Type2, or else report an error.

In what follows, I am focusing on <:< which turns out to be more useful, but just know that =:= is a thing and works in a very similar way.

The why and how of this feature is the subject of the rest of this article! So for now, let’s take this as a recipe, a trick if you will, while we look at how this can be useful in practice.

Let’s start with flatten on Option:

def flatten[B](implicit ev: A <:< Option[B]): Option[B]

What does flatten do, as per the documentation? It removes a level of nesting of options:

scala> val oo: Option[Option[Int]] = Some(Some(42))

oo: Option[Option[Int]] = Some(Some(42))

scala> oo.flatten

res1: Option[Int] = Some(42)

This doesn’t make much sense if the type parameter A of Option is not, itself, an Option-of-something. So what should happen if you call flatten on, say, an Option[String]? I see two possibilities:

- The

flatten method returns None.

- The compiler reports an error.

The authors of the Scala standard library picked option 2, and I think that it’s a good choice, because most likely calling flatten in this case is not what the programmer intends. And lo and behold, the compiler doesn’t let this pass:

scala> val oi: Option[Int] = Some(42)

oi: Option[Int] = Some(42)

scala> oi.flatten

<console>:21: error: Cannot prove that Int <:< Option[B].

oi.flatten

So we have a generic type, Option[+A], which has a method, flatten, which can only be used if the type parameter A is itself an Option. All the other methods (except orNull which is similar to flatten) can be called: map, get, etc. But flatten? Only if the type of the option is right!

One thing to realize is that we have something unusual here: a method which the compiler won’t let us call, not because we pass incorrect parameters to the method (in fact flatten doesn’t even take any explicit parameters), but based on the value of a type parameter of the underlying Option class. This is not something you see in Java, and you have probably rarely seen it in Scala.

Looking again at the signature of flatten, we can see how the recipe is applied: implicit ev: A <:< Option[B] reads “make sure that A is a subtype of Option[B]”, and, since A stands for the parameter type of Option, we have:

- in the first case “make sure that

Option[Int] is a subtype of Option[B]”

- in the second case “make sure that

Int is a subtype of Option[B]”

Obviously, Option[Int] can be a subtype of an Option[B], where B = Int (or B = AnyVal, or B = Any). On the flip side, there is just no way Int can be a subtype of Option[B], whatever B might be. So the recipe works, and therefore the constraint works.

To get the hang of it, let’s look at another nice use case , toMap on Traversable:

def toMap[K, V](implicit ev: A <:< (K, V)): Map[K, V]

Translated into English: you can convert a Traversable to a Map with toMap, but only if the element type is a tuple (K, V). This makes sense, because a Map can be seen as a collection of key/value tuples. It wouldn’t make great sense to create a Map just out of a sequence of 5 Ints, for example.

Similar rationales apply to the few other uses of <:< in the standard library, which all come down to constraining methods to work with a specific contained type only.

In light of these examples, I find that applying this recipe is easy, even though the syntax is a bit funny. But I can think of a few questions:

- Can’t we just use type bounds which I thought existed to enforce this kind of type constraints?

- If this is a pattern rather than a built-in feature, why does

<:< look so much like an operator? Does the compiler have special support for it?

- How does this whole thing even work?

- Is there an easier ways to achieve the same result?

Let’s look into each of these questions in order.

Question 1: Can’t we just use type bounds?

Lower and upper bounds

Type bounds cover lower bounds and upper bounds. These are well explained in the book Programming in Scala, so I won’t cover the basics here, but I will present some perspective on how they work.

As a reminder, lower and upper bounds are expressed with builtin syntax: >: and <: (spec). You can read:

T >: U as “type T is a supertype of type U” or “type T has type U as lower bound”T <: U as “type T is a subtype of type U” or “type T has type U as upper bound”

A puzzler

Let’s consider the following:

scala> def tuple[T, U](t: T, u: U) = (t, u)

tuple: [T, U](t: T, u: U)(T, U)

My tuple function simply returns a tuple of the two values passed, whatever their types might be. Granted, it’s not very useful!

What are T and U? They are type variables: they stand for actual types that will be decided at each call site (each use of the function in the source code). Here both T and U are abstract: we don’t know what they will be when we write the function. For example we don’t say that U is a Banana, which would be a concrete type.

If we pass String and Int parameters, we get back a tuple (String, Int) in the Scala REPL:

scala> tuple("Lincoln", 42)

res1: (String, Int) = (Lincoln,42)

Now let’s consider the following modification, which is a naive attempt at enforcing type constraints with type bounds:

def tupleIfSubtype[T <: U, U](t: T, u: U) = (t, u)

I know, it’s starting to be like an alphabet (and symbol) soup! But let’s stay calm: the only change is that instead of specifying just T as type parameter, we specify T <: U, which means “T must be a subtype of U”.

The intent of tupleIfSubtype is to return a tuple of the two values passed, like tuple above, but fail at compile time if the first value is not a subtype of the second value.

So does the newly added constraint work? Do you think that the compiler will accept to compile this?

tupleIfSubtype("Lincoln", 42)

Before knowing better, I would have thought that the compiler:

- would decide that

T = String

- would decide that

U = Int

- see the type constraint

T <: U, which translates into String <: Int

- fail compilation because obviously,

String is not a subtype of Int

But it turns out that this actually compiles just fine!

How can this be? Is the constraint not considered? Is it a bug in the compiler? A weird edge case? Bad language design? Or maybe, with T <: U, the U is not the same as the second U in the type parameter section? This can quickly be proven false:

scala> def tupleIfSubtype[T <: V, U](t: T, u: U) = (t, u)

<console>:7: error: not found: type V

def tupleIfSubtype[T <: V, U](t: T, u: U) = (t, u)

So the two Us are, as seemed to make sense intuitively, bound to each other (they refer to the same type).

The answer to this puzzler turns out to be relatively simple: it has to do with the way type inference works, namely that type inference solves a constraint system (spec).

What happens is that yes, I do pass String and Int, but it doesn’t follow that T = String and U = Int. Instead, the effective T and U are the result of the compiler working its type inference algorithm, given:

- the types of the parameters we actually pass to the function,

- the constraints expressed in the type parameter section,

- and, in some cases, the expression’s return type.

If I write:

scala> def tuple[T, U](t: T, u: U) = (t, u)

tuple: [T, U](t: T, u: U)(T, U)

scala> tuple("Lincoln", 42)

res3: (String, Int) = (Lincoln,42)

then yes: T = String and U = Int because there are no other constraints. But when I introduce an upper bound, there is a constraint, and therefore a constraint system. The compiler resolves it and obtains T = String and U = Any:

scala> def tupleIfSubtype[T <: U, U](t: T, u: U) = (t, u)

tupleIfSubtype: [T <: U, U](t: T, u: U)(T, U)

scala> tupleIfSubtype("Lincoln", 42)

res4: (String, Any) = (Lincoln,42)

We can verify that the resulting types satisfy the constraints:

String is a String of courseInt is a subtype of AnyString is also a subtype of Any

Phew! So this makes sense. It’s “just” a matter of understanding how type inference works when type bounds are present.

In the process we have learned that <: and >:, when used with abstract type parameters, do not necessarily produce results which are very useful, because the compiler can easily infer Any (or AnyVal or AnyRef) as solutions to the constraint system.

Question 2: Why does <:< look so much like an operator?

Lets dig a little deeper to understand how <:< works under the hood. Here is a simple type hierarchy used in the examples below:

trait Fruit

class Apple extends Fruit

class Banana extends Fruit

Parameter lists and type inference

Let’s start with a couple more things you need to know in Scala:

- Functions can have more than one parameter list.

- Type inference operates parameter list per parameter list from left to right.

In particular, an implicit parameter list can use types inferred in previous parameter lists.

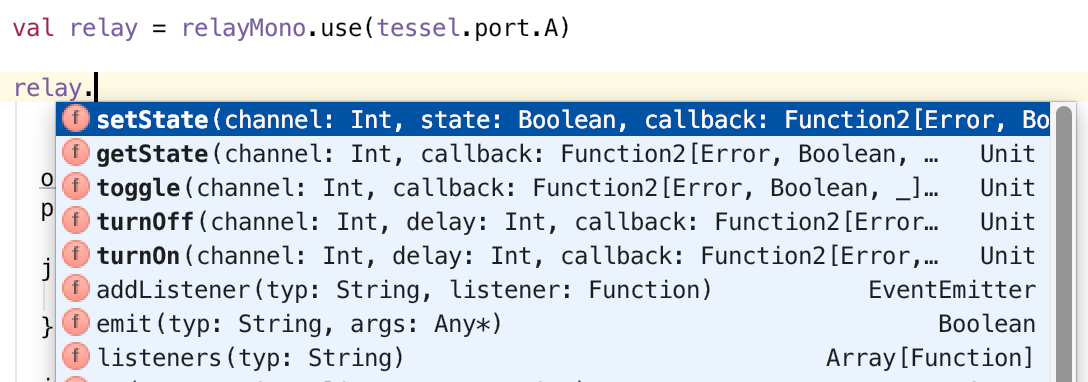

So let’s write the solution, without necessarily understanding it fully yet:

def tupleIfSubtype[T, U](t: T, u: U)(implicit ev: T <:< U) = (t, u)

This function has two parameter lists:

(t: T, u: U)(implicit ev: T <:< U)

Because type inference goes parameter list by parameter list, let’s start with the first one. You notice that there are no >: or <: type bounds! So:

T is whatever specific type t has (say T = Banana)U is whatever specific type u has (say U = Fruit)

Infix types

Looking at the second parameter list, we have to clear a hurdle: what kind of syntax is T <:< U? This notation is called an infix type (spec). “Infix” just means that a type appears in the middle of two other types, the same way the + operator appears in the middle in 2 + 2. The type in the middle (the infix type proper) can be referred to a an infix operator. Instead of this operator being a method, as is the case in general in Scala, it is a type.

Let’s look at examples. You probably know types from the standard library such as:

Map[String, Fruit]

Either[String, Boolean]

These exact same types can be written:

String Map Fruit

String Either Boolean

The infix notation makes the parametrized type look like an operator, but an operator on types instead of values. Other than that, it’s just an alternate syntax, and really nothing to worry about!

So based on the above:

T <:< U

means the the same as:

<:<[T, U]

A symbolic type name

Now, what is a <:<? It’s a type: the same kind of stuff as Map or Either, in other words, typically a class or a trait. It’s just that this is a symbolic name instead of an alphabetic identifier like Map. It could as well have been called SubtypeOf, and maybe it should have been!

The implicit parameter

So once we reach the second (and implicit) parameter list:

(implicit ev: T <:< U)

we see that there is a parameter of type <:<, which itself has two type parameters, T and U. These are the same T and U we have in the first parameter list. They are bound to those, and these are known because type inference already did its magic on the first parameter list. Concretely, T is now assigned the type Banana and U the type Fruit!

What the implicit parameter list says is this: “Find me, somewhere in the implicit search path, an implicit val, def, or class of type <:< which satisfies <:<[T, U]”. And because T and U are now known, we need to find an implicit match for <:<[Banana, Fruit].

The trick is to manage to have an implicit definition in scope which matches only if there is a subtype relationship between T and U. For example:

| T |

U |

Compiler Happiness Level |

Banana |

Fruit |

happy |

Apple |

Fruit |

happy |

Int |

Anyval |

happy |

Apple |

Banana |

unhappy |

String |

Int |

unhappy |

If we manage to create such an implicit definition, the constraint mechanism works. And we already know that the clever engineers who devised this have found a way to create such an implicit definition!

By the way, we can play with this in the REPL using the standard implicitly function, which returns an implicit value for the given type parameter if one is found:

implicitly[Banana <:< Fruit] // ok

implicitly[Apple <:< Fruit] // ok

implicitly[Int <:< Anyval] // ok

implicitly[Apple <:< Banana] // not ok

implicitly[String <:< Int] // not ok

To summarize, we now have a pretty good level of understanding and we know that:

- we are talking about a library feature

- which relies on an implicit parameter

- with a funny symbolic type operator

<:<.

And we also know that the magic that makes it all work lies in the search for a matching implicit definition: if it is found, the subtyping relationship holds, otherwise it doesn’t and the compiler reports and error.

Question 3: How does this whole thing even work?

We could stop here and be happy to use <:< like a recipe, as if it was a core language feature. But that wouldn’t be very satisfying, would it? After all, we still miss the deeper understanding of how that magic implicit is defined, and why an implicit search for it may or may not match it. So let’s keep going!

The implementation

Let’s look at the implementation of <:<, which we find in the Scala Predef object :

@implicitNotFound(msg = "Cannot prove that ${From} <:< ${To}.")

sealed abstract class <:<[-From, +To] extends (From ⇒ To) with Serializable

private[this] final val singleton_<:< = new <:<[Any, Any] {

def apply(x: Any): Any = x

}

implicit def $conforms[A]: A <:< A = singleton_<:<.asInstanceOf[A <:< A]

Wow! Can we figure it out? Let’s try.

Which implicit?

Let’s think about a simpler case of implicit search:

def makeMeASandwich(implicit logger: Logger) = ...

implicit def findMyLogger: Logger = ...

val mySandwich = makeMeASandwich

The compiler, when you write makeMeASandwich without an explicit parameter, looks for an implicit in scope of type Logger. Here, the obvious matching implicit is findMyLogger, because it returns a Logger. So the compiler selects the implicit and in effect rewrites your code as:

val mySandwich = makeMeASandwich(findMyLogger)

The same mechanism is at work with implicit ev: T <:< U: the compiler must find an implicit of type T <:< U (or <:<[T, U] which is exactly the same). And there is only one implicit definition with type <:<-of-something in the whole standard library, which is:

implicit def $conforms[A]: A <:< A

Now there is a bit of a twist, because the implicit is of type <:<[A, A], with a single type parameter A, which in addition is abstract. Anyhow, this means that our function parameter ev of type <:<[T, U] must, somehow, “match” with <:<[A, A].

If we ask ourselves: what does it take for this implicit of type <:<[A, A] to be successfully selected by the compiler? The answer is that one should be able, for some type A to be determined, to pass a value of type <:<[A, A] to the parameter of type <:<[T, U]. Another way to say this is that <:<[A, A] must conform to <:<[T, U]. If we can’t do this, the implicit search will fail.

Variance

How does this conformance work? This takes us to the notion of variance, which is always a fun thing. Consider a Scala immutable Seq. It is defined as trait Seq[+A]. The little + says that if I require a Seq[Fruit], I can pass a Seq[Banana] just fine:

def takeFruits(fruits: Seq[Fruit]) = ...

takeFruits(Seq(new Banana))

This is called covariance (the subtyping of the type argument goes in the same direction as the enclosing type). Without the notion of covariance and contravariance (where subtyping of the type argument goes in the opposite direction as the enclosing type), you:

- either can never write code like this (everything is invariant)

- or you have an unsound type system

Besides collections, functions are another example where variance and contravariance matter. Say the following process function expects a single parameter, which is a function of one argument:

def process(f: Banana ⇒ Fruit)

I can of course pass to process a function with these exact same types:

def f1(f: Banana): Fruit = f

process(f1)

But Scala’s support for subtyping also applies to functions: a function can be a subtype of another function. So I can pass a function with types different from Banana and Fruit without breaking expectations as long as the function:

- takes a parameter which is a supertype of

Banana

- returns a value of a subtype of

Fruit

For example:

def f2(f: Fruit): Apple = new Apple

process(f2)

This is the magic of variance, and you can convince yourself that it makes sense from the point of view of the process function: expectations won’t be violated.

Functions are not a special case in Scala from this point of view: a function of one parameter is defined (in a simplified version) as a trait with the function parameter as contravariant and the result as covariant:

trait Function1[-From, +To] { def apply(from: From): To }

Putting everything together

After this detour in variance land, let’s get back to <:< and the implicit parameter. The implicit <:<[A, A] will conform to the parameter <:<[T, U] if it follows the variance rules. So what’s the variance on <:<[T, U] in Predef?

<:<[-From, +To]

This is the same as Function1[-From, +To] and in fact <:< extends Function1! So our problem comes down to the following question: if somebody requires a function:

T ⇒ U

what constraints must be satisfied so I can pass the following function:

A ⇒ A

With variance rules, we know it will work if:

A is supertype of T- and

A is subtype of U

Written in terms of bounds:

T <: A <: U

Which means of course that T <: U: T must be a subtype of U!

To summarize the reasoning: the only eligible implicit definition in scope which can possibly be selected by the compiler to pass to our function is selected if and only if T is a subtype of U! And that’s exactly what we were looking for!

You can look at this from a slightly more general angle, which is that a function A ⇒ A can only be passed to a function T ⇒ U if T is a subtype of U. You can in fact test the matching logic very simply with the built-in identity function:

val f: Banana ⇒ Fruit = identity // ok

val f: Fruit ⇒ Banana = identity // not ok

The same works with $conforms, which returns an <:<, which is also an identity function:

val f: Banana ⇒ Fruit = $conforms // ok

val f: Fruit ⇒ Banana = $conforms // not ok

So it is a neat trick that the library authors pulled off here, combining implicits and conformance of function types to implement constraint checking.

The nitty-gritty

The rest of the related code in Predef is about defining the actual <:< type and creating a singleton instance returned by def $conforms[A], because in case the implicit search matches, it must return a real value after all.

You could write it minimally (using <::< in these attempts so as to not clash with the standard <:<):

sealed trait <::<[-From <: To, +To] extends (From ⇒ To) {

def apply(x: From): To = x

}

implicit def $conforms[A]: A <::< A =

new <::<[A, A] {}

But oops, the compiler complains:

scala> def tupleIfSubtype[T, U](t: T, u: U)(implicit ev: T <::< U) = (t, u)

<console>:23: error: type arguments [T,U] do not conform to trait <::<'s type parameter bounds [-From <: To,+To]

def tupleIfSubtype[T, U](t: T, u: U)(implicit ev: T <::< U) = (t, u)

The good news is that the following version, using an intermediate class, works:

sealed trait <::<[-From, +To] extends (From ⇒ To)

final class $conformance[A] extends <::<[A, A] {

def apply(x: A): A = x

}

implicit def $conforms[A]: A <::< A =

new $conformance[A]

So this works great, with a caveat: every time you use my version of <::<, a new instance of the anonymous class is created. Since we just want an identity function, which works the same for all types and doesn’t hold state, it would be good to use a singleton so as to avoid unnecessary allocations. We could try using an object, since that’s how we do singletons in Scala, but that’s a dead-end because objects cannot take type parameters:

scala> implicit object Conforms[A] extends (A ⇒ A) { def apply(x: A): A = x }

<console>:1: error: ';' expected but '[' found.

implicit object Conforms[A] extends (A ⇒ A) { def apply(x: A): A = x }

So in the end the standard implementation cheats by creating an untyped singleton using Any, and casting to [A <:< A] in the implementation of $conforms. Here is my attempt, which works fine:

private[this] final object Singleton_<::< extends <::<[Any, Any] {

def apply(x: Any): Any = x

}

implicit def $conforms[A]: A <::< A =

Singleton_<::<.asInstanceOf[A <::< A]

The actual Scala implementation opts for using a val instead of an object (maybe to avoid the cost associated with an object’s lazy initialization):

private[this] final val singleton_<:< = new <:<[Any, Any] {

def apply(x: Any): Any = x

}

implicit def $conforms[A]: A <:< A =

singleton_<:<.asInstanceOf[A <:< A]

We are only missing one last bit:

@implicitNotFound(msg = "Cannot prove that ${From} <:< ${To}.")

sealed abstract class <:<[-From, +To] ...

This helps provide the user with a nice message when the implicit is not found. From a syntax perspective, it is a regular annotation, which applies to the abstract class <:<. The annotation is known by the compiler.

So here we are: the implementation is explained! It’s a bit trickier than it should be in order to prevent extra allocations. I confess that I am a bit disappointed that there doesn’t seem to be a way to avoid an instanceOf: even though it’s local to the implementation and therefore the lack of safety remains under control, it would be better if it could be avoided.

An implicit conversion

One thing you might wonder is what to do with the ev parameter. After all, a value must be passed to the function when the implicit is found (when it’s not found, the compiler blows up so ev doesn’t need an actual value).

A first answer is that you don’t absolutely need to use it. It’s there first so the compiler can check the constraint. That’s why it’s commonly called ev, for “evidence”: its presence stands there as a proof that something (an implicit) exists.

Nonetheless, ev must have a value. What is it? It’s the result of the $conforms[A] function, which is of course of type <:<[T, U]. And we have seen above that <:< extends T ⇒ U. So the result of $conforms[A] is a function, which takes an A and returns an A, that is, an identity function. And it not only returns a value of the same type A, but it actually returns the same value which was passed (that’s the idea of an identity function).

And you see that in the implementation:

def apply(x: Any): Any = x

It follows that ev has for value an identity function from T to U: it takes a value t of type T and returns that same value but with type U. This is possible, and makes sense, as we know that T is a subtype of U, otherwise the implicit wouldn’t have been found.

But there is more: ev is also an implicit conversion from T to U (from Banana to Fruit). How so? Because it has the keyword implicit in front of it, that’s why!

To contrast with regular type bounds, if you write:

def tupleIfSubtype[T <: U, U](t: T, u: U) = ...

the compiler knows that T is a subtype of U, thanks of the native semantic of <:. But with <:<, the compiler knows nothing of the sort based on the type parameter section.

However the presence of the implicit ev function makes it possible to use the value t of type T as a value of type U. The subtype relationship can be seen as an implicit conversion. This is much safer than using t.asInstanceOf[U]. You could also be extra-explicit and write:

ev(t)

So you can write:

def tToU[T, U](t: T, u: U)(implicit ev: T <:< U): U = t

or:

def tToU[T, U](t: T, u: U)(implicit ev: T <:< U): U = ev(t)

Without the implicit conversion, the compiler complains:

scala> def tToU[T, U](t: T, u: U): U = t

<console>:10: error: type mismatch;

found : t.type (with underlying type T)

required: U

def tToU[T, U](t: T, u: U): U = t

You can see how Option.flatten makes use of the ev() function:

def flatten[B](implicit ev: A <:< Option[B]): Option[B] =

if (isEmpty) None else ev(this.get)

In summary, all these features fall together to produce something that makes a lot of sense and is useful.

Question 4: Is there an easier ways to achieve the same result?

There is at least one other way something like what <:< does can be achieved. The idea is that a method such as flatten does not need to be included on the base class or trait, in this case Option. Instead, Scala has, via implicit conversions, what in effect achieves extension methods (AKA the “extend my library” pattern).

So say that such an extension method is only available on values of type Option[Option[T]]:

implicit class OptionOption[T](val oo: Option[Option[T]]) extends AnyVal {

def flattenMe: Option[T] = oo flatMap identity

}

If we try to apply it to Some(Some(42)), the method is found and the flattening works:

scala> Some(Some(42)).flattenMe

res0: Option[Int] = Some(42)

If we try to apply it to Some(42), the method is not found and the compiler reports an error:

scala> Some(42).flattenMe

<console>:13: error: value flattenMe is not a member of Some[Int]

Some(42).flattenMe

But I see a few differences with the <:< operator:

- You need to create one implicit class for each type supporting a conversion. In the case of

Option, for example, you need one implicit class taking an Option[Option[T] to support flatten, and another implicit class to support orNull. So this requires a bit more boilerplate than <:< per method.

- I am not sure whether there something similar to

@implicitNotFound to report a better error in case of problem.

So why not do it this way? I think that a good case can be made that it is easier to understand in the case of the relatively simple examples we have seen so far.

UPDATE 2015–12–10: Somebody kindly pointed out that at the time generalized type constraints were implemented, Scala didn’t yet have value classes or implicit classes. Missing value classes meant boxing overhead when running extension methods, while missing implicit classes just meant more boilerplate. So using an implicit value class as I did above was not a great option at the time.

On the other hand, <:< is a more flexible library feature which you can reuse easily and even combine with other implicits, like in this example using Shapeless:

def makeJava[F, A, L, S, R](f: F)(implicit

ftp: FnToProduct.Aux[F, L => S],

ev: S <:< Seq[R],

ffp: FnFromProduct[L => JList[R]]

)

Finally, when using type bounds, the constraints expressed with <: and >: can only apply to the method type parameters (or class type parameters when they are used on a class). This is very useful, as we have seen. But when using <:<, you can constrain any two types in scope, and even impose multiple such constraints. Your imagination is the limit:

trait T[A, B] {

type C

type D

def constrainTwoTraitParams (implicit ev: A <:< B) = ()

def constrainTraitParamAndTypeMember(implicit ev: A <:< C) = ()

def constrainTwoTypeMembers (implicit ev: C <:< D) = ()

def constrainMore[Y](c: Y) (implicit ev1: A <:< B, ev2: Y <:< C) = ()

}

class C extends T[Banana, Fruit] {

type U = Fruit

type V = String

}

You can even go further and constrain not only these types directly, but higher-order types, as in this (math- and symbol-heavy) example from Miles Sabin:

def size[T](t: T)(implicit ev: (¬¬[T] <:< (Int ∨ String))) = ???

In this case, the constraint is not directly on the T type parameter, but on ¬¬[T].

This might be, after all, how the term “generalized type constraint” gets its name.

Perspectives

We have seen how regular type bounds:

- behave when using abstract type parameters

- but don’t work to actually enforce certain useful constraints.

We have also seen how we can use instead a generalized type constraint expressed with <:<:

- to implement methods which can only be used when types are aligned in a certain way

- and how

<:< is not a built-in feature of the compiler, but instead a library feature implemented via a smart trick involving implicit search and type conformance.

Finally, we have considered:

- how the simple use cases in the standard library could be implemented differently

- but also how

<:< is a more general tool.

So is <:< is worth it? Should it be part of the standard library, and should Scala developers learn it?

I think that the feature suffers from the fact that is is not properly documented, explained, and put in perspective. It also suffers from being a symbolic name with no agreed upon way to pronounce it!

The standard library uses of <:< could be replaced with “extension methods”, which would achieve the same result via Scala features which are easier to understand and familiar to most Scala programmers. I think that this argues against the presence of <:< in the standard library, especially at the level of Predef, and if this was introduced today, my inclination would be to recommend leaving it to third-party libraries such as Shapeless which actually benefit the most from this kind of advanced features.

On the plus side, when used <:< as a recipe, it is easy to understand and useful, and I can’t help but being impressed that generalized type constraints are implemented at the library level, and that they can emerge from powerful underlying language features such as type inference and implicits.

This is typical of Scala, and in line with the principle of Martin Odersky that it is better to keep the core language small when possible. So even though the explanation of how <:< works might seem a bit tricky, you can take comfort in thinking that in other languages this might be compiler code, not library code. But I also understand how some programmers might be bothered by all the machinery behind features like this.

As for me, I am keeping generalized type constraints in my toolbox, but I like seeing the feature as a gateway to a more in-depth understanding of Scala. I hope this post will help others along this path as well!

Did I get anything wrong? Please let me know!